THE American WESTERN

By Jeffrey-Baptiste Tarlofsky

By Jeffrey-Baptiste Tarlofsky

Lesson 7 consists of nine video lectures and transcripts of those lectures, and seven film excerpts. Start with excerpt #1 from Bend of the River and continue down the page in sequence until you reach the end of the lesson.

レッスン7は9本のビデオレクチャー(レクチャーのテキストがビデオレクチャーの下に記載されています)と7 本の動画で構成されています。

このレッスンは、ページをスクロールダウンしながら最初から順番に動画を見たりテキストを読んでください。

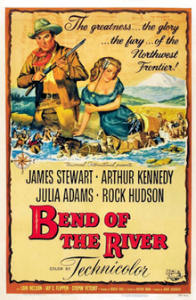

Directed by: Anthony Mann

Screen play by: Borden Chase

Based on: Bend of the Snake 1950 novel by Bill Gulick

Starring: James Steward, Arthur Kennedy, Julie Adams, Rock Hudson

Music by: Hans J. Salter

Running time: 91 minutes

Budget: Unknown

Box office: $3 million

Part 1 – Stagecoaches were the way people in the west travelled from one town to the next before there were railroads, but to travel the thousand miles from Independence, Missouri to Salt Lake City, Utah for example people traveled by wagon train. The challenge of the journey to the west is one of the most popular and romantic themes for Western films. A wagon train was a group of wagons (usually Calistoga or covered wagons) traveling together for mutual protection and economy. In the early days when the road was not clear marked or easy to follow the wagon trains hired professional guides such as Glyn McLyntock, the character we just saw in the excerpt from director Anthony Mann’s film, A Bend Of the River. McLyntock is played by legendary actor Jimmy Stewart. (see images #1 and #2)

Just as John Ford and John Wayne teamed up to make fourteen films together, nine of which were Westerns, Anthony Mann and Jimmy Stewart made eight films together five of which were Westerns. Stewart was a very different kind of actor than John Wayne. While Stewart was one of the most important actors in the Western genre, he also played comic roles, tragic roles, romantic roles and he appeared regularly in half a dozen different genre in addition to the western. He was Anthony Mann’s favorite leading man, but he was also favored by Frank Capra and Alfred Hitchcock and he worked with many other famous directors including George Cukor, Billy Wilder and Otto Preminger. John Wayne was unquestionably the greatest star of the Classic Western genre, but in The American Film Institute’s overall rankings of the greatest male film actors of all times Jimmy Stewart is ranked third, while John Wayne is ranked at number thirteen. Similarly, John Ford was unquestionably the greatest director of Western films by far, but Anthony Mann is one of the men who tied for second best in that genre.

Directors make many choices when they make a film and one choice Anthony Mann made was to make A Bend Of The River a color film. We really have not paid much attention to this yet in this class, but we will as the course progresses. Before 1939, color films were very rare and exotic, but in that year Hollywood released two films in color which are still magnificent to watch just for their color: The Wizard of Oz and Gone with The Wind. Just look at this excerpt from The Wizard of Oz to appreciate the contrast between Black and white and color. Dorothy’s house has been picked up by a tornado and moved from her home state of Kansas to the magical land of Oz . (The Wizard of Oz YouTube link.)

Part 2 – So color changed things in a major way, but it isn’t quite as simple as saying “color makes everything better” because, quite frankly, it often doesn’t. For example: Pause for a moment and ask yourself whether Stagecoach would have looked better if it had been filmed in color? Why or why not? Write your thoughts down in your notes. Pause.

It is my opinion that If John Ford had used color to make Stagecoach the film would have looked hideous. The fact that the film is in black and white enhances our feelings of nostalgia for the era and it also enables us to appreciate the stark beauty of the landscapes Ford films. Black and white also draws our attention to shapes and movements in quite a different way than color film does. Let us say that black and white film simplifies things while forcing us to pay attention to details in a way color film simply doesn’t. There is more discipline in black and white photography and cinematography.

Allow me to draw a comparison with Japanese art. What is the difference between a gorgeous color byōbu produced by the Kano school of painters on gold leaf (image #3) and a simple kakejuku produced by, oh, let’s say, Musashi Miyamoto (image #4)? Yes, That Musashi. He was also a painter as well as a swordsman, you know.

So….which is better? That is, of course, a ridiculous question that has no answer. But we can ask “which do you like better?” and there is no wrong answer. But better questions are, “how are they different? What do they do? How do they effect us differently?” I think the same questions can be asked of black and white and color films. As the course continues, I will ask you to think about those questions.

For now, we can say that for some films color works better while for others black and white works better. This was usually the director’s choice (although color film was more expensive so directors had to consider that in their decision making as well). A Bend of the River is one example of a film where color worked better, Stagecoach is an example of a film where color would have been a disaster.

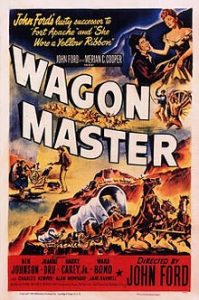

Our main attraction in this lesson is yet another black and white by John Ford: Wagon Master (1950). We will return to both Jimmy Stewart and Anthony Mann later in the course. Let’s see how Ford begins his film.

Directed by: John Ford

Written by: Patrick Ford and Frans S. Nugent

Starring: Ben Johnson, Joanne Dru, Harry Carey, Jr., Ward Bond

Music by: Richard Hageman

Distributed by: RKO Radio Pictures, Inc.

Running time: 86 minutes

Part 3 – It was unusual, though not unheard of, for a film to simply begin the story before any credits rolled. In this case, Ford begins by introducing not the stars of the film, but the outlaw Cleggs family. Perhaps he wanted us to immediately contrast their wickedness with the goodness of his heroes.

Then Ford rolls the credits while we hear the theme music for the film. Music is important in all Ford films, but in Wagon Master the entire feeling of the film is linked to the music and especially the songs. The film score was the work of Richard Hageman, Ford’s most frequent musical collaborator. Hageman also wrote the wonderful score for Stagecoach. He did the scores for seven Ford films including five of the fourteen westerns. According to Wikipedia “Songs are important in Wagon Master. Critic Dennis Lim has written, “Practically a musical, Wagon Master is filled with frequent song and dance interludes and accompanied by a steady stream of hymns and ballads, performed by the popular country group The Sons of the Pioneers. Song writer Stan Jones wrote four original songs that were performed by The Sons of the Pioneers for the film’s soundtrack.” I think it is a bit of an exaggeration to call the film a musical, but music is important in the film. I will say more later.

Then we meet Travis and Sandy, young horse traders who are on the way to the small town of Crystal City. Like Buck, the stagecoach driver, these are working men of the west and it doesn’t surprise us that a simple math problem like 30 x 12 challenges Sandy because he has probably had very little education.

Wagon Master is an unusual Ford film for the time because Ford did not use big name stars in it. Ford’s usual stars were either John Wayne or Henry Fonda, but neither of them are in this film. In fact, it is the only feature length sound Western Ford made without a big star. Instead, he used members of his stock company (actors who were in many of his films as supporting actors). The lead parts are played by three Ford stock company regulars; Ben Johnson, Harry Carey, Jr. and Ward Bond. Despite the lack of a big name star some critics (including your humble servant) consider it to be one of Ford’s best films. It has been called a visual poem rather than a story. It is also the best film depicting the challenges faced by those who ventured west by wagon train.

Part 4 – The Mormons forbid the use of alcohol, tobacco, bad language, gambling and all other forms of wickedness! Even though Sandy and Travis are good, honest, hard-working men, they drive a hard bargain for their horses. But, Elder Wiggs (by the way, “Elder” was a title given the lowest rank of the clergy in Mormonism ) was willing to pay their price because he was hoping to hire them as wagon masters to guide his expedition. This is also why he asks Travis and Sandy if they drink alcohol or use tobacco or use bad language. He would not hire men who did those things. Travis turns down the offer because he thinks the Mormons won’t be able to cross the desert and get past the mountains in a wagon train. Besides he wants to play poker! Gambling! Elder Wiggs leaves in utter (if wistful) disgust.

Wagon Master is based on real history. The Mormons were a relatively new religious group who were violently persecuted in the midwest states of Ohio, Illinois and Missouri. To escape religious persecution, they began to head to the west in 1846. Ford’s film is based on the much later Mormon expedition known as the San Juan Mission or the Hole-in-the-Rock Expedition, which took place in late 1879 and early 1880. They were headed towards what is today southeastern Utah. Interestingly, the events in this film happen at almost exactly the same time as the fictional events in Stagecoach.

Part 5 – We see that the persecution is no joke. The Mormons are being forced to leave the town under threat from armed men. You will notice that such persecution is a theme in John Ford’s films. Doc and Dallas were forced to leave their town in a similar way In Stagecoach.

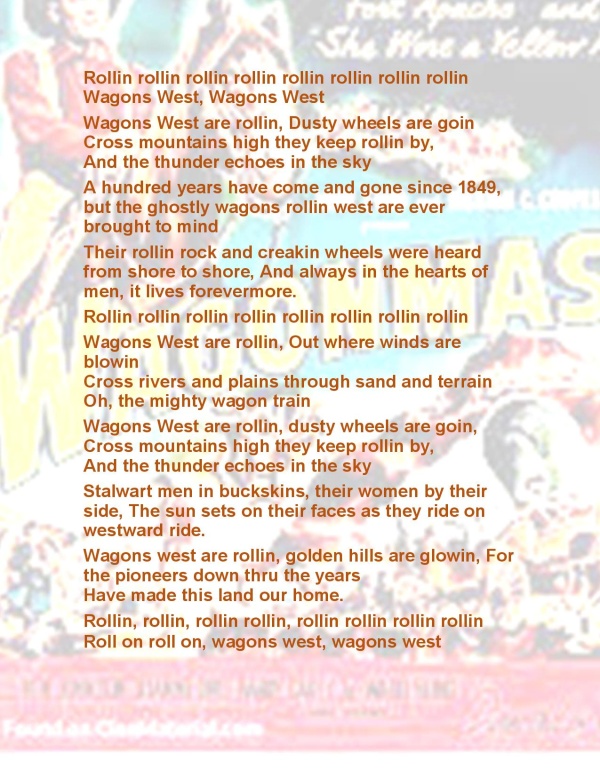

Sandy and Travis have a change of heart and decide to help the Mormons on their journey (for a price). Ford charmingly has them reach agreement about this by breaking into a song. Then we have some wonderful scenes of the wagon train crossing the river with the song “Wagons West” being sung by the Sons of the Pioneers. This really is a magical combination. As I mentioned earlier, Richard Hageman composed the music in this film as he had for Stagecoach. Hageman shared something with many of the other men who composed music for American Westerns…he was not born in America! Hageman was born in the Netherlands and had all of his musical training there. He was a purely classical musician with absolutely no knowledge of American folk music when he arrived in America at age twenty-five. Yet, he composed the scores for five of John Ford’s Westerns, the first being Stagecoach and the last being Wagon Master. Let’s briefly compare key elements of both the compositions. Please go to the following links on YouTube.

Stagecoach: 1939 (Suite and Variation From “Stagecoach” 1939 Film Soundtrack)

Part 6 – Notice that the tempo (speed) of the music matches the different modes of transportation? The stagecoach moves very fast throughout the film so the music does, too. But the wagon train moves at a much slower pace so the music does as well. But I would add that in both cases the music makes us aware that we are moving, either quickly or slowly, both films are about getting somewhere, either a town only three days away, or a valley six months away (which is actually how long it took the Mormons to get to their destination), so the music is full the feeling of movement .

Now have a look at the actual lyrics for Wagons West

As all songs do, it sounds better when sung. But the lyrics (the words themselves), like the music, match the action we see on screen as the wagon train crosses the river.

The next big challenge the wagon train faces is crossing a desert. It is a long, slow, hot thirsty crossing and on the way they rescue a small group of four people in one wagon who ran out of water on the crossing. They are two old men, one old woman and one young woman. To celebrate the safe crossing of the desert and the rescue of the strangers there is a dance party that night.

Part 7 – But then the party is interrupted by unwelcome strangers. We know who they are, of course, and so do Sandy and Travis. Ford slowly gives us close ups of all the main characters at this point…each of the Cleggs, Elder Wiggs, Sandy, Travis and Brother Jackson. That is eight closeups, and in each case we know exactly who the good guys are and who the bad guys are. The Cleggs attach themselves to the wagon train like leeches.

Several days later there is another challenge. They meet a group of heavily armed Navajo warriors. But through careful diplomacy (and thanks to Travis and Sandy speaking Navajo) they avoid a confrontation and are even invited to the Navajo camp as guests that night. This is one of the very few times at this stage in his career that Ford depicts Indians in a positive way.

Part 8 – Elder Wiggs probably saved many lives by ordering the whipping of Reece Cleggs. If he had not done so the Navajo would have been forced to take revenge themselves and there probably would have been a battle. The whites certainly would have lost that battle. Considering that there were over 200 crimes in the old west for which the penalty was death by hanging in the 1880s, whipping was a relatively mild punishment…at least physically. You would not die from a whipping. But whipping was considered to be disgraceful for the man who was whipped precisely because it was a milder punishment. Whipping was usually the punishment a school master or father gave to a boy who committed some minor offense like not doing his homework.

Whipping an adult man was treating him like a child and so in addition to being physically painful it also brought the man disgrace. It was an insult to his honor. Of course, that is exactly why Elder Wiggs orders Reece to be whipped. His attempted rape of the Navajo woman would have been both a physical crime against her but it would also have been a crime against her honor. This concept of ”honor” in the old west can be compared to the Japanese concept of “meiyo” among the samurai. One is expected to both behave “honorably” but also to defend one’s “honor” and the honor of one’s family, tribe or clan. Recall that Hatfield was willing to kill Lucy Mallory in order to protect her “honor”. In this film the Navajo would kill Reece and a lot of other people for offending the honor of one of their women. Elder Wiggs understands that the way to make sure the Navajo don’t do this is by “dishonoring” the would-be rapist by whipping him. The Navajo accept this and do not demand an even stricter punishment. Elder Wiggs certainly saved Reece’s life. But we cannot expect the Cleggs to understand or appreciate this.

At last the wagon train faces the final obstacle, a mountain that seems almost impossible to pass. Yet, as we will see, they actually manage to create a path to allow them to go over the mountain. This is based in actual history. The Mormons really did carve a narrow road through (not over) a mountain and managed to get their wagons through. It took them six months the do this rather than the six weeks they originally planned. But they got through.

In the film, the Cleggs are actually their last obstacle.

Part 9 – Unlike the final gunfight in Stagecoach, Ford shows us the deaths of each one of the Cleggs. This poses an interesting moral problem in the film. If the Mormons reject violence completely shouldn’t they reject Travis and Sandy for using violence to save them? At this point I have to tell you that John Ford’s film is not historically accurate here. The Mormons in the film refuse to carry guns, but in fact the Mormons who made these journeys in wagon trains were heavily armed and quite willing to defend themselves. There are even cases in which the Mormons were the aggressors. Ford is romanticizing the history to make his story more interesting. But he is also not telling us the truth. It is a problem that plagues much of his work and the whole Western film genre. A lot of what we see is just made up.

But that doesn’t mean Ford didn’t make a great movie! And it doesn’t mean his characters don’t grow and develop in ways as interesting as those who rode on the stagecoach grow and develop. Travis and Sandy started the film as horse traders and gamblers and men with guns. By the end of the film Travis throws away his gun. He and Sandy will both get married and become Mormons. I suppose that is supposed to be a happy ending.

But here’s how I want to end the lecture for this lesson. The problem of when violence is justified is one that John Ford and many other Western film makers confronted in their films. The simple fact is that the West was an incredibly violent place and good people were often the victims of that violence. In many Western films the only answer to the violence of evil men like the Cleggs is the violence of good men like Travis and Sandy. This is a theme in almost every Western film I can name. That concludes my lecture for lesson number seven.