THE American WESTERN

By Jeffrey-Baptiste Tarlofsky

By Jeffrey-Baptiste Tarlofsky

Lesson 28 consists of 9 video lectures and transcripts of those lectures, and 8 film excerpts. Start with the lecture, Part 1 and continue down the page in sequence until you reach the end of the lesson.

レッスン28は、9本のビデオレクチャー(レクチャーのテキストがビデオレクチャーの下に記載されています)と8本の動画で構成されています。

このレッスンは、最初のLecture Part 1から順番に動画を見たりテキストを読んでください。

Part 1 – Just as John Ford shaped the Western more than any other film director, so did he also shape the sub-genre of the Western concerned with the American Indian. In films like Stagecoach and Drums on the Mohawk, that image is very negative. In these films, except when an Indian is working against a common enemy as we saw the Cheyenne scout doing at the very beginning of Stagecoach, or unless he has completely abandoned his own culture and people and agreed to serve the interests of the white invaders, as Blue Black does throughout Drums On The Mohawk, the Indians are portrayed in an almost completely negative light. In other words, unless they are betraying their own people, the Indians are viewed as the “bad guys”. But we will see, there is a double standard when it comes to whites who betray other whites.

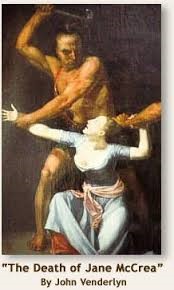

In both Stagecoach and Drums On The Mohawk, Ford places a special emphasis on the potential danger of rape that white women such as Lucy Mallory or Lana Martin faced if they were captured by the Indians. However, in 1939, it would have been impossible for Ford to say this directly in his films. Because of the censorship in Hollywood at the time, Ford could not even use the word “prostitute” in Stagecoach when Dallas, his female lead, was in fact, a prostitute. Similarly, the censorship rules forbade him from even using the word “rape”. Moreover, the prejudices against mixed-race relationships of any kind (even including…perhaps, especially including rape) made it impossible for Ford to do anything but hint at the horrors of such a thing as interracial rape. Perhaps because Ford began his career in the age of silent films, he was especially good at hinting in a way that made something clear to the audience without needing to use words. In Stagecoach, it is enough for Ford to show us Hatfield looking at his last bullet and then slowly pointing his gun at the praying Lucy Mallory for us to know why he is doing this. American audiences would have understood that Hatfield wished to spare Lucy the horrors of being a white woman captured by the Indians. The audience not only understood what Hatfield was about to do but strongly approved of it. Better dead than raped by Indians was the attitude. Similarly, Lana’s screams of sheer terror when she sees Blue Back are not because she fears he will “murder” her but because she fears she will be taken prisoner with all that would entail.

We should not be too quick to dismiss this fear of rape as exaggerated either. I have already explained that rape was and still is a weapon of terror used to show the men of one society that they cannot protect their wives, mothers, and sisters from the enemy. But rape was obviously also a direct attack on the women themselves. Women, we should recall, are largely responsible for creating the conditions for civilization by maintaining the home and raising children. Destroy women and you destroy the culture they maintain. Sexual assault on the women of an enemy culture often entailed torture and humiliation. Those who lived through this ordeal would, of course, be badly traumatized. In many cases, these women were not killed but returned to their homes and villages after they had been made pregnant by their tormentors. What would it mean to give birth to the child of the enemy who raped you? It would often mean the woman herself was sometimes shunned in her own community. “Why”, people would ask, “didn’t you kill yourself rather than submit to being raped?”. This “blaming the victim” for the crime of the enemy is often almost as traumatic for the women as what the enemy did to them. There are still societies in the world today where a woman who has been raped can be charged with a crime…the crime of allowing herself to be raped! However, I would not have you believe things are not changing. In 2008, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 1820, which noted that “rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute war crimes, crimes against humanity or a constitutive act with respect to genocide”. This is real progress.

We should not be too quick to dismiss this fear of rape as exaggerated either. I have already explained that rape was and still is a weapon of terror used to show the men of one society that they cannot protect their wives, mothers, and sisters from the enemy. But rape was obviously also a direct attack on the women themselves. Women, we should recall, are largely responsible for creating the conditions for civilization by maintaining the home and raising children. Destroy women and you destroy the culture they maintain. Sexual assault on the women of an enemy culture often entailed torture and humiliation. Those who lived through this ordeal would, of course, be badly traumatized. In many cases, these women were not killed but returned to their homes and villages after they had been made pregnant by their tormentors. What would it mean to give birth to the child of the enemy who raped you? It would often mean the woman herself was sometimes shunned in her own community. “Why”, people would ask, “didn’t you kill yourself rather than submit to being raped?”. This “blaming the victim” for the crime of the enemy is often almost as traumatic for the women as what the enemy did to them. There are still societies in the world today where a woman who has been raped can be charged with a crime…the crime of allowing herself to be raped! However, I would not have you believe things are not changing. In 2008, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 1820, which noted that “rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute war crimes, crimes against humanity or a constitutive act with respect to genocide”. This is real progress.

To return to our films, let me pose a question: despite what audiences in 1939 might have thought, what do we think when we see Hatfield preparing to shoot Lucy Mallory? Perhaps we ask ourselves “what right does this man have to do that? Shouldn’t the choice to live or die be Lucy’s?” Hatfield obviously has no intention of asking her what she wants. Ford has Hatfield shot just before he can shoot Lucy and at just that moment Lucy hears the sound of the bugle and knows they are going to be rescued. This sudden rescue at the last possible moment became so famous that it led to the widespread use of the term “here comes the cavalry” to mean “rescued at the last moment”. But was this also a way for Ford to reject the idea that a woman should be killed or kill herself to avoid capture by the Indians? As a Catholic, Ford would have found suicide to be unacceptable on moral grounds, but would he have thought the same about a “mercy killing” by Hatfield meant to save Lucy from gang rape, torture, and eventual death at the hands of the Apache? Moreover, did the Indians really do such terrible things to prisoners so as to make someone want to kill themselves rather than be captured? Let’s take a look at a brief excerpt from Ford’s film, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) to see if this was so.

Before screening the excerpt, let me remind you that I said that when I was a little boy I was afraid of werewolves, aliens, and Indians. This is the film that really made me afraid of Indians more than any other. The film stars John Wayne (of course) Ben Johnson and Harry Carey Jr. (the two stars of Wagon Master). Here, they are spying on a group of Indians to find out how the Indians are getting modern repeating rifles.

Directed by John Ford

Screenplay by Frank Nugent and Laurence Stallings

Based on The Big Hunt 1947 story in The Saturday Evening Post

War Party 1948 in The Saturday Evening Post by James Warner Bellah

Starring John Wayne, Joanne Dru, John Agar, Ben Johnson, Harry Carey, Jr.

Narrated by Irving Pichel

Music by Richard Hageman

Running time: 103 minutes

Part 2 – “Indian Agents” were government agents who were supposed to be in charge of keeping the Indians peaceful by buying things the Indians produced and selling them things they needed or simply delivering government supplies to them in order to keep them on the reservations. Indian agents were notoriously corrupt and often stole the supplies from the Indians, but in this film, Ford shows us an Indian agent who is so corrupt he is actually willing to sell guns to the Indians so they can make war on the whites! This man is only interested in making money by illegally selling stolen weapons to the Indians. It seems that in the nine years since he made Stagecoach and Drums on the Mohawk, Ford has come to believe that some white men could act just as badly as the Indians. But let me remind you of the double standard* Ford is maintaining. Indians who betray Indians are “good guys’, but whites who betray whites are “bad guys”. Let’s see what happens to white men who betray their own kind to the Indians.

Part 2 – “Indian Agents” were government agents who were supposed to be in charge of keeping the Indians peaceful by buying things the Indians produced and selling them things they needed or simply delivering government supplies to them in order to keep them on the reservations. Indian agents were notoriously corrupt and often stole the supplies from the Indians, but in this film, Ford shows us an Indian agent who is so corrupt he is actually willing to sell guns to the Indians so they can make war on the whites! This man is only interested in making money by illegally selling stolen weapons to the Indians. It seems that in the nine years since he made Stagecoach and Drums on the Mohawk, Ford has come to believe that some white men could act just as badly as the Indians. But let me remind you of the double standard* Ford is maintaining. Indians who betray Indians are “good guys’, but whites who betray whites are “bad guys”. Let’s see what happens to white men who betray their own kind to the Indians.

A double standard is a code or policy that favors one group or person over another. Double standards are unfair. … A standard is a way of evaluating someone, and a double standard is two-faced. It’s like having a rule that applies to some people one way and another way to others

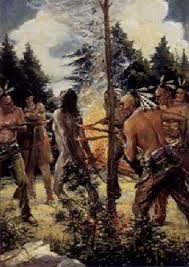

Part 3 – A white man willing to sell guns to the Indians is a traitor to his own people. But I remind you that Blue Back was also a traitor to his own people. In much of literature and drama, the fate of a traitor is that he himself is betrayed and Ford shows us exactly this when the Indian Chief shoots Mr. Renders in the middle of their negotiations. It was horrifying enough to see Mr. Renders shot with the arrow, but the Indians then shoot his translator and then….well, now you will see why I had nightmares about this as a child.

Part 4 – The Indians make a sort of game of rolling the two wounded men through the campfire. By the way, this is historically accurate. The Apache really did do this.

This was too much for me. I had bad dreams about this for months! Just as shocking as what the Indians do to the men is what John Wayne’s character does. He speaks to one of his soldiers who thinks he is asking for a rifle to shoot the two men…a mercy killing to end their suffering. This was what Hatfield wanted to do in order to spare Lucy being tortured. But, he does not want the rifle, he asks for the soldier’s knife so he can cut some chewing tobacco! The point is that the John Wayne character is allowing the Indians to torture the two white men to death because he thinks they deserve it. By selling the guns to the Indians they have earned the punishment they get. His remark that chewing tobacco can “turn a man’s stomach” is again, ironic. He is saying that he can stomach (endure) the torture of the two men (because they deserve it). The other soldier asks for some tobacco to chew as well in order to show that he can also “stomach” (endure) the sight of the men being tortured.

The fact that these men would not help the two men being tortured even though they were very bad men bothered me as much as the fact the Indians were torturing them. Professor Tarlofsky simply does not think anyone should be tortured for any reason. I thought so when I was eight years old watching this movie and I have not changed my mind since. We are seeing a very dark side of John Ford in this scene, but we will see much darker in another film he makes eight years later which we will study in our next lesson.

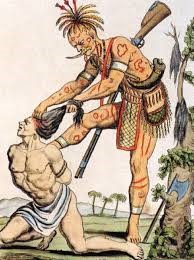

Indians torturing/killing captives with fire.

John Ford is not the only director of Westerns to show us the cruelty of the Indians. Howard Hawks’ great epic, Red River shows Thomas Dunson losing the only woman he ever loved to an Indian attack on a wagon train, and fourteen years later Matthew Garth finds the woman he will love when he rescues her wagon train from a similar attack. In both attacks there is, again, an emphasis placed on the special danger women face from Indian attacks. Red River was released in 1948 and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon in 1949. One year later, another of the great Western directors, Anthony Mann, released his film Winchester ’73 (1950). The similarities to She Wore A Yellow Ribbon are striking. The story is about how a special rifle, a Winchester ’73 1 in 1,000, passes from one character to another in the film. You have read about this weapon in your homework. Anthony Mann named his film after “the gun that won the west”.

Directed by Anthony Mann

Screenplay by Borden Chase and Robert L. Richards

Story by Stuart N. Lake

Starring James Stewart, Shelley Winters, Dan Duryea, Stephen McNally

Music by Walter Scharg

Running time: 92 minutes

Box office: $2,250,000

Part 5 – The Winchester model 1873 was known as “the gun that won the West”. Handguns were certainly the weapons white men most frequently used to fight each other, but it was the Winchester that whites most often used to fight the Indians. In the days of the musket, the absolutely fastest rate of fire a very competent professional soldier could achieve with a musket was one shot every 15 seconds. That was for highly trained professionals. For a normal man, it could take a minute or longer to reload a musket. Moreover, the musket was an unreliable weapon with both poor accuracy and short distance. However, about one hundred years after the American Revolution was fought with muskets, came the Winchester ’73, a fast shooting, long-range and highly accurate repeating rifle. An Indian warrior with bow and arrow could shoot further, faster, and more accurately than most men could with a musket. But, the Winchester reversed that balance of power. How fast was the Winchester? To see, go to Youtube “How a Winchester 1873 works”.

I am sure you recognize the star of the film, Jimmy Stewart, who plays the part of Lin McAdam. Lin and his partner are chasing a man named Dutch Henry Brown. Lin and Dutch are such deadly enemies that the only reason they do not shoot at each other on sight is that the town marshal has confiscated their handguns and rifles while the shooting contest is going on. Lin wins the shooting contest against Dutch, who says it is a shame to waste such a gun shooting rabbits to which Lin replies that is better than shooting men in the back, (We later learn that Dutch shot Lin’s father in the back and killed him, which is why Lin is so determined to take revenge). It appears Dutch and his men mean to make a fast getaway, so Lin prepares to chase them. However, Dutch has something else in mind as you will see in the next excerpt.

I am sure you recognize the star of the film, Jimmy Stewart, who plays the part of Lin McAdam. Lin and his partner are chasing a man named Dutch Henry Brown. Lin and Dutch are such deadly enemies that the only reason they do not shoot at each other on sight is that the town marshal has confiscated their handguns and rifles while the shooting contest is going on. Lin wins the shooting contest against Dutch, who says it is a shame to waste such a gun shooting rabbits to which Lin replies that is better than shooting men in the back, (We later learn that Dutch shot Lin’s father in the back and killed him, which is why Lin is so determined to take revenge). It appears Dutch and his men mean to make a fast getaway, so Lin prepares to chase them. However, Dutch has something else in mind as you will see in the next excerpt.

Part 6 – Dutch and his men are obviously in trouble without their guns or ammunition. But even these obvious outlaws are contemptuous of the Indian trader. A white man who sells guns to the Indians is seen as a traitor even by outlaws like Dutch and his gang. But they need the Indian trader’s weapons to safely cross through Indian territory to their destination. They also know that Lin and his partner are trailing them and they will need weapons to fight them if they catch up.

The Indian trader is an extremely cunning man. He offers to buy the Winchester from Dutch and offers him $300 plus a handgun and rifle for each of the three men. In the film, this is supposed to be a very low offer for the Winchester ’73, 1 in a 1,000. But the movie gets the numbers wrong. The actual price of a Winchester ’73, 1 of 1,000 in the year 1873 was only $100, (which was still three months pay for a cowboy, remember). In fact, the year that the film was made, 1950, an antique Winchester ’73, 1 of 1,000, could be bought at auction for as little as $1,000. However, after the movie came out there was a huge increase in the value of these antique guns. I checked the auction prices for the Winchester ’73, 1 in 1,000, and the estimates run from $230,000 to $450,000. Yikes!

Part 7 – The Indian Trader in Winchester ’73 is doing the same thing the Indian Agent in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon did. He is illegally selling guns to the Indians when he knows full well the Indians will use the guns to attack white settlers and soldiers. The Indians are still the “bad guys” in this movie, but Anthony Mann lets his Indian chief explain (to the audience) why the Indians want to kill the white people: “In peacetime, you steal our land and in wartime, you kill our women”. Both accusations are perfectly true, but it was unusual for a Western to allow this to be said. It is an early sign that things were changing in Hollywood. However, when the chief sees the prized Winchester, he does not hesitate to simply take what he wants. Again, the punishment for a white traitor is that he is himself betrayed. In this case, the Indian trader is scalped* rather than burned alive.

*Scalping is the repulsive custom of removing the skin from the top of a human skull in one piece usually by cutting around the edges and then lifting the entire piece off by the hair. The scalp would then be dried or smoked to preserve it. Scalping was, indeed, originally an Indian custom. It was a way to prove that a warrior had killed his enemy. The European custom had been to take the entire head of a conquered enemy, but they adopted the scalping practice from the Indians because it was easier to preserve and carry scalps rather than entire heads.

Japanese samurai also took the heads of their enemies, but if it were inconvenient to take the entire head, they would take just the nose and upper lip of the enemy. In North America, however, whites were the first to offer “bounties” (cash rewards) for Indian scalps with the price ranging from $25-$60 per Indian scalp. In Western films, it is usually the Indians who are shown practicing scalping, but a few films were honest enough to show that this was also a custom (and trade) among whites.

Part 8 – Lin has respect for the strategy the Indians use to win their battles but thinks he has a plan that might defeat them using the three repeating rifles he and the other men have. Nevertheless, he fears what might happen if they lose the battle, and when he gives his handgun to the only woman in the camp. He also gives her a very serious look. Again, we have non-verbal communication. He doesn’t need to say anything because the look he gives her “speaks a thousand words”. She smiles bravely and says, “I know about the last one”. Of course, she means that she understands that she should commit suicide with the last bullet rather than risk capture by the Indians. Once again, we have Hollywood’s almost neurotic emphasis on the potential rape of white women at the hands of non-white men.

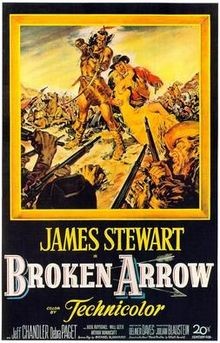

In contrast to all the films about Indians we have seen so far that show the Indians at their worst, the film Broken Arrow (1950) shows a very significant shift in how the American Indian was portrayed in the American Western. This film is an early example of films that try to present a more balanced view of the conflict with the Indians. These films depict the Indian as a so-called noble savage*.

*The concept of the noble savage originated in the 18th-century with the Enlightenment philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau. He believed the original “man” was free from sin, appetite, or the concept of right and wrong, and that those deemed “savages” were not brutal but “noble”. We might think of the film image of the noble savage as being similar to how nature programs depict tigers. The tiger is certainly dangerous, but the emphasis is on the tiger’s place in nature and his beauty and power.

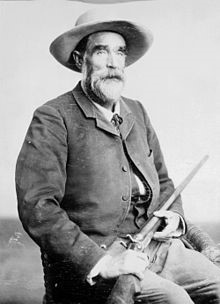

Broken Arrow is highly unusual for a Hollywood western because it is closely and accurately based on true historical events. The film concerns a peace treaty that was negotiated between the Apache Indian Chief Cochise and a white man named Tom Jeffords who represented the U.S. army. The film stars Jimmy Stewart as Jeffords

The Real Tom Jeffords

Directed by Delmer Daves

Written by Elliott Arnold (novel Blood Brother) Michael Blankfort (front name for Albert Maltz)

Starring James Steward, Jeff Chandler, Debra Paget

Music by Hugo Friedhofer

Running time: 93 minutes

Box office: $3,550,000

Part 9 – The film was directed by the much-underrated director, Delmar Daves. Daves does not enjoy the same reputation as the likes of Anthony Mann or Howard Hawks, but he should. Daves direction of this film was exceptional. It is as much in the direction and characterization as in the story that the power of this film lies. As mentioned, Cochise and Jeffords were real historical figures. The story is also one of the very few in the history of white-Indian relations that actually had a peaceful outcome for a time.

Let us closely examine the excerpt. Cochise is portrayed by the very handsome actor Jeff Chandler. This is historically accurate. Cochise was well known for being a very tall and handsome man.

Cochise also speaks to Jeffords in clear, easy to understand English. This is very important. Every other Indian we have heard speak English has spoken it badly in some way, as Blue Back did in Drums on The Mohawk when he said, “Me go now”, or as the drunken Mohawk warriors did when they say, “burn house”. On the other hand, Cochise speaks English slowly and carefully but with complete fluency. Of course, this is because Cochise is being played by an English speaking actor, (Jeff Chandler), who actually went on to play Cochise in two more films. Cochise begins by stating he is the leader of his people and he does not lie to them.

He speaks with such sincerity that we do believe him, which is more than we can say about many of our own leaders past or present! Cochise has a forceful personality and appears to be an honorable man. Everything about how Delmar Daves films this scene favors Cochise. As Jeffords sits down the camera looks up at Cochise from a high angle. We literally look up to this man as Jeffords does. When he sits it is “Indian style” (which also happens to be “Buddha style” in your culture). He looks directly at the camera. This is a highly unusual camera angle. When a director films an actor this way it gives the impression that the actor is actually speaking to the audience in the movie theater. Directors only use this angle when they have a very important message for the audience.

Then there is the fact that this film is in color. There is a huge debate in film circles about whether the greatest westerns are in color or black and white. My answer is, of course, that both can be great, but that they do different things. When John Ford gives us images of Monument Valley in black and white, we feel we are transported back to a certain place and time. When Shane confronts Wilson in Shane we have almost a duel between black and white in a color film, but Shane, as I pointed out, is bathed in a soft golden light while Wilson is in a harsher light. This effect could only be achieved because the film was in color. But before Shane was bathed in that golden light in 1953, there was Cochise in Broken Arrow in 1950 bathed in the same golden light. In my humble opinion, the power of both these scenes greatly depends on the use of both color and lighting. The message to the audience is as simple as “white hat good, black hat bad”. The message is “golden light good”. It is a beautiful piece of filmmaking and it is used to fully humanize an Indian character for perhaps the first time in Hollywood History.

In our next and final lesson, we will see where John Ford takes us in two very different films about the Indians.